BRIEF ENCOUNTERS

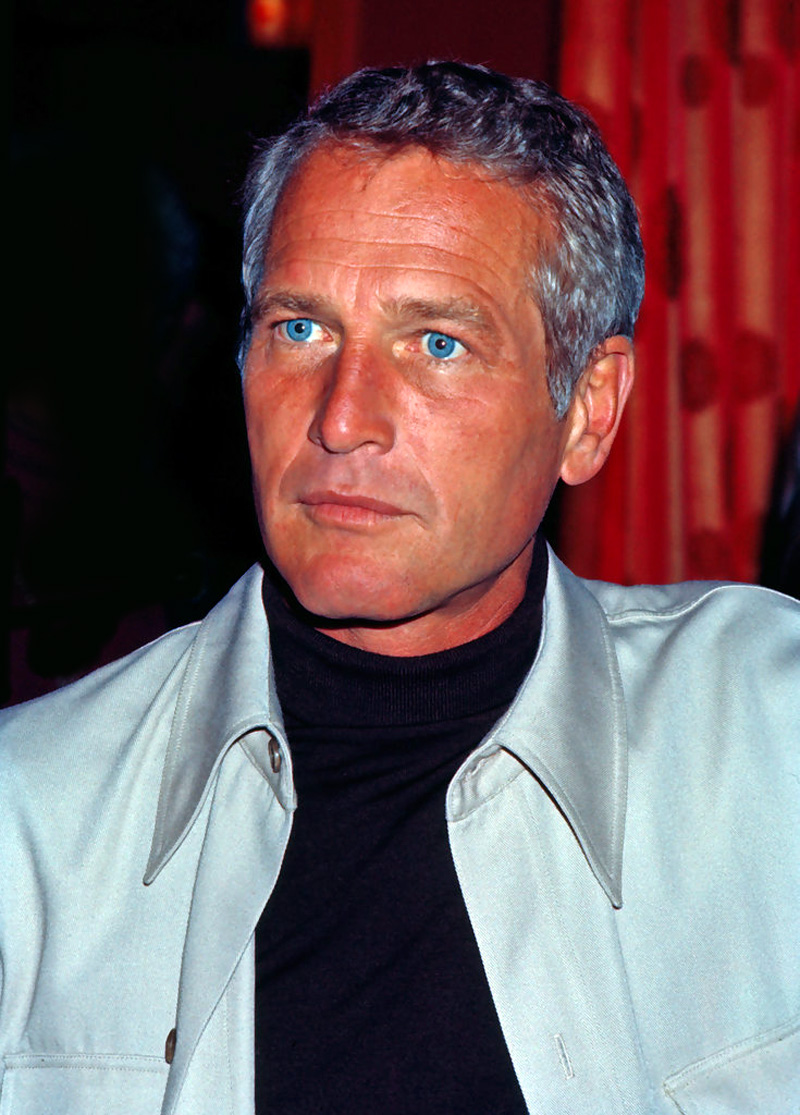

Paul Newman

Paul Leonard Newman (January 26, 1925 – September 26, 2008) was an American actor, film director, race car driver, and entrepreneur. He was the recipient of numerous awards including the Cecil B DeMille Award, three Golden Globes, a BAFTA Award and an Academy Award.

Born in Shaker Heights, an upscale suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, Newman attended the Yale School of Drama before studying at the Actors Studio in Manhattan under Lee Strasberg.

His major film roles included The Hustler (1961), Hud (1963), Harper (1966), Cool Hand Luke (1967), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972), The Sting (1973), The Towering Inferno (1974), Slap Shot (1977), and The Verdict (1982). A ten-time Oscar nominee, Newman was finally awarded an Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in The Color of Money (1986).

In 1958, he married his second wife, Joanne Woodward, also a celebrated movie star, who was awarded an Academy Award two months after their wedding for her role in Three Face of Eve. They were married for 50 years and shared three children before Paul died in 2008 at the age of 83. His body was cremated and his remains given to family and friends.

I met Paul Newman in the early 1990s. By then, he was an internationally recognized A-List movie star, but one who abhorred the celebrity lifestyle of Beverley Hills. He preferred to live a quiet life away from the limelight in a converted farmhouse in the coastal village of Westport, Connecticut, where he would politely return his neighbors greetings if he was spotted running an errand in town, but would hide his most famous features to avoid detection.

I was asked to drive up to his Hole in the Wall Gang Camp in Ashford, Connecticut and deliver a generous corporate donation into his hands. The camp, founded by the movie star in 1988, is a charitable organization established as a summer camp for children aged 7-15 suffering with cancer and other serious ailments. It’s intended to be a place where they can enjoy all the pleasures of summer camp and, in the words of the actor, “raise a little hell,” in what may be for some of them the last few months of their lives.

The Hole in the Wall Gang was a real-life gang in the 1880s American Wild West, which took its name from the Hole-in-the-Wall Pass in Johnson County, Wyoming, where several notorious outlaw gangs, whose crimes covered horse and cattle theft, stagecoach and highway robbery, store and bank robbery, had their hideouts.

The 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which starred Robert Redford, Katherine Ross, and Paul Newman, features the hideout that the two bandits escape from to avoid arrest by a posse of federal authorities in dogged pursuit. The American Film Institute ranked the movie among the greatest westerns of all time.

Of course, I knew the name Paul Newman and was familiar with some of his movies when I drove up to rural northwest Connecticut that day, but, typically, I knew little more about the man I was about to meet.

I pulled up at a central cluster of wooden buildings that looked like a movie set from a forgotten western. Someone pointed to a building where I would most likely find the star and suggested I go there and wait outside.

A short while later, a screen door swung open and a little scruffy guy stepped out to greet me. I thought he was the janitor. But he stuck out his hand saying, “Hi! I’m Paul Newman.” I stepped back in surprise. I don’t know if I expected James Bond in a tux or what, but this person was totally unexpected. He was shorter and thinner than I had imagined, was wearing grubby sweats, a Yankees baseball hat that had seen better days, and aviator sunglasses hiding his eyes.

A few polite exchanges later, he said, “Come on, let’s go to lunch.” We ambled across the compound toward what turned out to be the camp’s dining hall, already crowded with dozens of noisy children and camp counsellors. We walked in without fanfare and sat down where we could at one of the less crowded trestle tables. As we did so, he removed his hat and glasses revealing his instantly recognizable features: close-cropped silver-gray hair and ice-blue eyes. Turning them toward me, he stood up smiling and murmured quietly in an off-hand way, “Excuse me for a minute, the children expect me to say hello.”

He paced confidently toward a space in the center of the room as if he were going on stage at the Old Vic. His audience, immediately recognizing him, grew quieter with each step he took. Soon the din had quietened to a respectful silence. When he had their full attention, he looked around the hall and boomed in his distinctive drawl, “Are you all having a good time?” The response was raucous. They cheered, clapped, banged on the tables, and roared “YES!”

He spoke a few more words, promising he would come to watch them play and would meet every one of them soon. With a wave, he walked back to his seat to another resounding roar of approval. The children’s love and admiration for him was palpable.

Sitting back down beside me, he took a moment to describe the camp’s mission. “It’s all about helping them reach beyond the barrier of their illness,” he began. “Their illness makes them retreat behind that barrier. They’re quiet and reserved and feel unable to do very much at all. Our job is to get them pass that, and we almost always succeed.”

Not surprisingly perhaps, given their success rate, the demand to attend the camp is high. Newman gave me the statistics. “We take in a new batch of kids for a one-week session several times each summer,” he said. “In total, about 20,000 children every year, many of them inner-city kids. When they get here, it maybe the first time they can truly enjoy the outdoors. They get to go horseback riding, boating, swimming, and fishing. They can try archery, sports, crafts, and, of course, theater,” he added with a wide grin. “But, more about that later. I’ll take you over there.”

I asked him how all this got started. I knew some of the story but I wanted to hear it in his own words.

He told me it all began with a salad dressing he “cooked up” in a tub in his garage with his Westport neighbor and long-time pal American author, playwright, and biographer Aaron Hotchner. “We’d pour the stuff into old wine bottles and give them away as Christmas gifts,” he chuckled.

Much to their surprise, their concoction became a huge hit. So much so, in 1982 the pair decided to co-found Newman’s Own, setting it up as a charitable organization. “We decided to give away all the profits to those who needed it. I thought if it made a million bucks, I’d be more than happy.... It’s making a lot more than that,” he said, shaking his head as if he still couldn’t believe it. “Let me show you.”

We walked outside to begin a tour. “You’ve got to remember,” he said, “despite the happy faces you see all around here, these kids are suffering and many are terminally ill...” We arrived at a building and peeked in through the windows. “This is a fully equipped emergency care facility,” he told me proudly. “We have a doctor and nurse on hand here 24/7 and a helicopter out back that can fly a kid to specialist care in Manhattan if need be... and… that happens.”

He mentioned the dormitories. “There’s so much money coming in, the kids’ beds even have Ralph Lauren blankets on them!” he chuckled. “Nothing is too good.”

We walked toward another building that turned out to be a professional-grade theater, fully equipped with sophisticated sound and light systems.

We sat down in two of the hundreds of seats lined up facing the empty stage, and chatted about his time as an actor and some of the great movies he’d made that I thought were his most memorable, especially Butch Cassidy. “You know, we were never paid any residuals for that movie,” he grumbled. “Do you know how many times that’s been rerun? Over and over again,” he sighed. “And we’ve never been paid an additional penny.”

But you’re a Hollywood legend!” I said, astonished. “You’re an industry icon! Surely you’ve got the clout to change that.”

No... I don’t,” he replied, slowly but emphatically. “It doesn’t matter who you are, the studios can shut you out in a heartbeat and you’ll never know it’s happened.”

We both went quiet. I could see I’d hit a nerve and it was time to change the subject. I told him how impressed I was with the space around us that seemed to me to have all the makings of a Broadway theater. “ Yea, it does,” he drawled. “It’s pretty much state-of-the-art, and we use it all the time. The camp staff coaches the kids during their time here so they can put on a show for friends and family at the end of their stay.” He paused, getting a little misty eyed. “It’s heart-warming to watch them,” he said, “ but a little sad at the same time. All that young promise…”

Now with tears in his eyes, he turned to me and said quietly, “It doesn’t matter about the movies and all that, this is my real legacy… and I’ve made sure it will last long after I’m gone.”

When he spoke those words, I don’t think he had any real idea just how massive a legacy he would leave and just how long his dream for the kids would endure. If he had, I’m certain he wouldn’t have changed a thing.

The Newman’s Own brand now markets more than a hundred products worldwide, with all profits going to charity. Since its start in 1982, the Newman’s Own Foundation has not only continued to maintain The Hole in the Wall Camp, brightening the final days of thousands of children from all walks of life, it has given well over half a billion dollars to thousands of other charities helping millions more around the world every year.

Paul Newman died of cancer in September of 2008, victim of a terminal disease himself like so many hundreds of children whose last dark months in this world he tried to brighten.